“DIGGIN’ IN THE FILES: WU-TANG CLAN” – BY BILL ADLER

EFN said let it be the Wu this time, so I duly started digging in my files about them. As ever, I wanted to go back as early as possible, because the early stuff is going to be rarer than whatever is written after a given act blows up, and because I believe, generally, that the rarer materials are intrinsically interesting.

In my files, the earliest materials on the Wu-Tang Clan include a short review of their first single in The Source in April of ’93 and a Loud Records ad from the fall of 1993. They also contain a short review of their first album in Rap Sheet from February of 1994 and, from that same month, a lengthy feature story about the crew in Rap Pages by Cheo Coker.

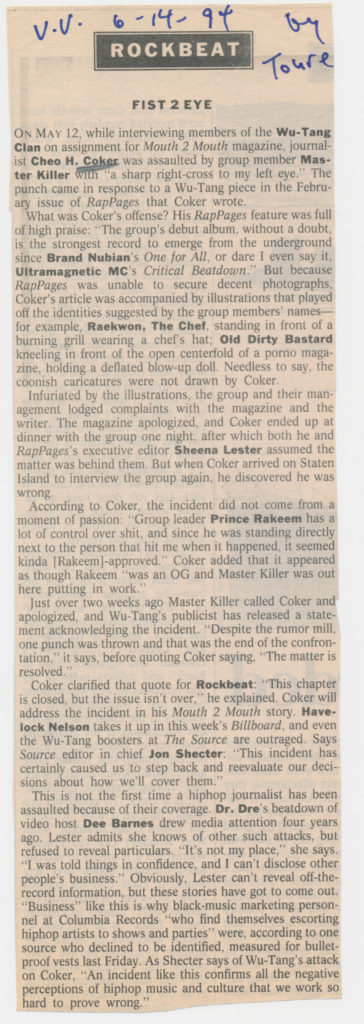

So far so good. But then came a zig. Turns out that the Wu felt dissed by the illustrations accompanying Cheo’s piece, which led, in early May of ’94, to Master Killer punching Cheo in the face, which naturally led to a shit-storm of coverage of, and commentary about, this act of violence. I was worried, then, that this edition of “Digging” would turn out to be little more than a replay of the last installment, which focused on the press generated by KRS-One’s attack on PM Dawn’s Prince Be.

Then came the zag. In January of 1995, Toure wrote a dual review of Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx and Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s Conspiracy for the Village Voice. At least, it sorta looks like a review. In actuality, it’s a very deep piece – half-sociology, half-psychoanalysis — concerning “the hip hop crew as the center of the world.” It is where this column ends up.

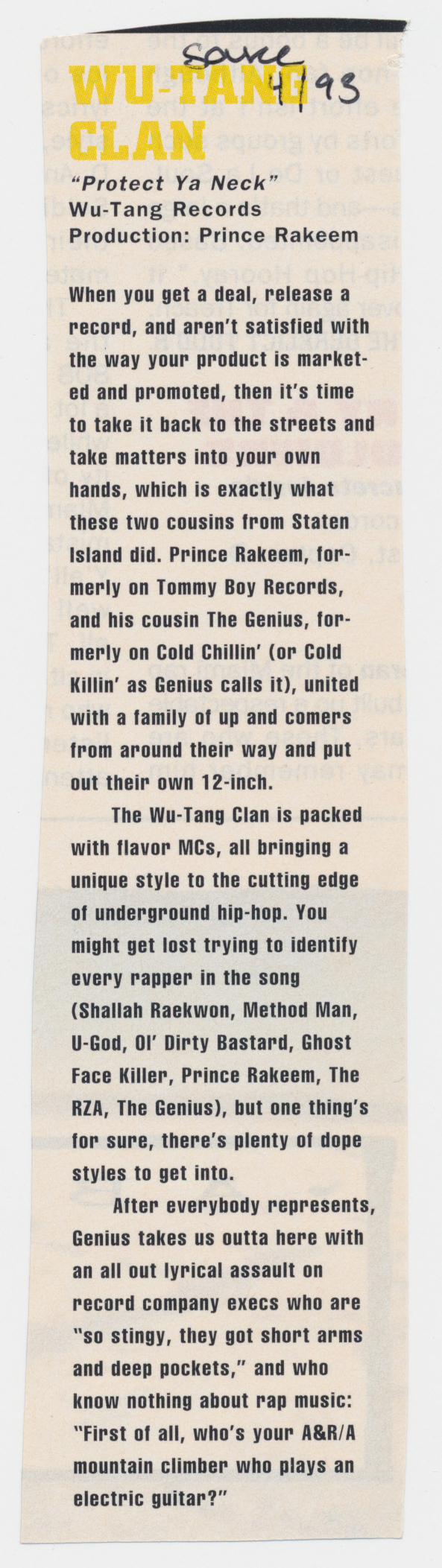

But before we get to the articles themselves, let’s set the stage. The core of the Wu-Tang Clan is a three-man crew of cousins from Staten Island. We have come to know these gents as the RZA, the GZA, and Old Dirty Bastard. Their first steps into the arena were as solo artists. In 1991, the RZA, calling himself Prince Rakeem, released an EP on Tommy Boy entitled Ooh I Love You Rakeem. That same year, the GZA, calling himself The Genius, released a full album on Cold Chillin’ entitled Words From the Genius. Neither of these projects set the world on fire. The artists, typically, blamed the labels. (For details, check out the GZA’s verse on “Protect Ya Neck.”)

Their next steps were far from typical. They assembled a nine-man crew from around the way, dubbed themselves the Wu-Tang Clan, and proceeded to produce “Protect Ya Neck” b/w “Method Man” — the very first Wu-Tang single — themselves. Then, in ’92, when none of the rap labels to whom they took the single wanted to put it out, they released it on their own label.

The single (reproduced above) earned a positive review in the April ’93 issue of The Source, which declared that these new jacks were “bringing a unique style to the cutting edge of underground hip-hop.”

A month later the single was re-released on Steve Rifkind’s Loud Records. The following fall Loud bought an ad announcing the imminent release of the Wu’s first album. (It was second-billed to Tha Alkaholiks’s 21 & Over, which was already in stores.)

It was November of ’93 when Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) hit the streets. By then, the Wu had devised a plan that allowed them, at least on paper, to retain much more than the usual amount of control over their careers. The group would record for one label. The individual members would put out solo albums on different labels. That way they’d never have all their eggs in one basket.

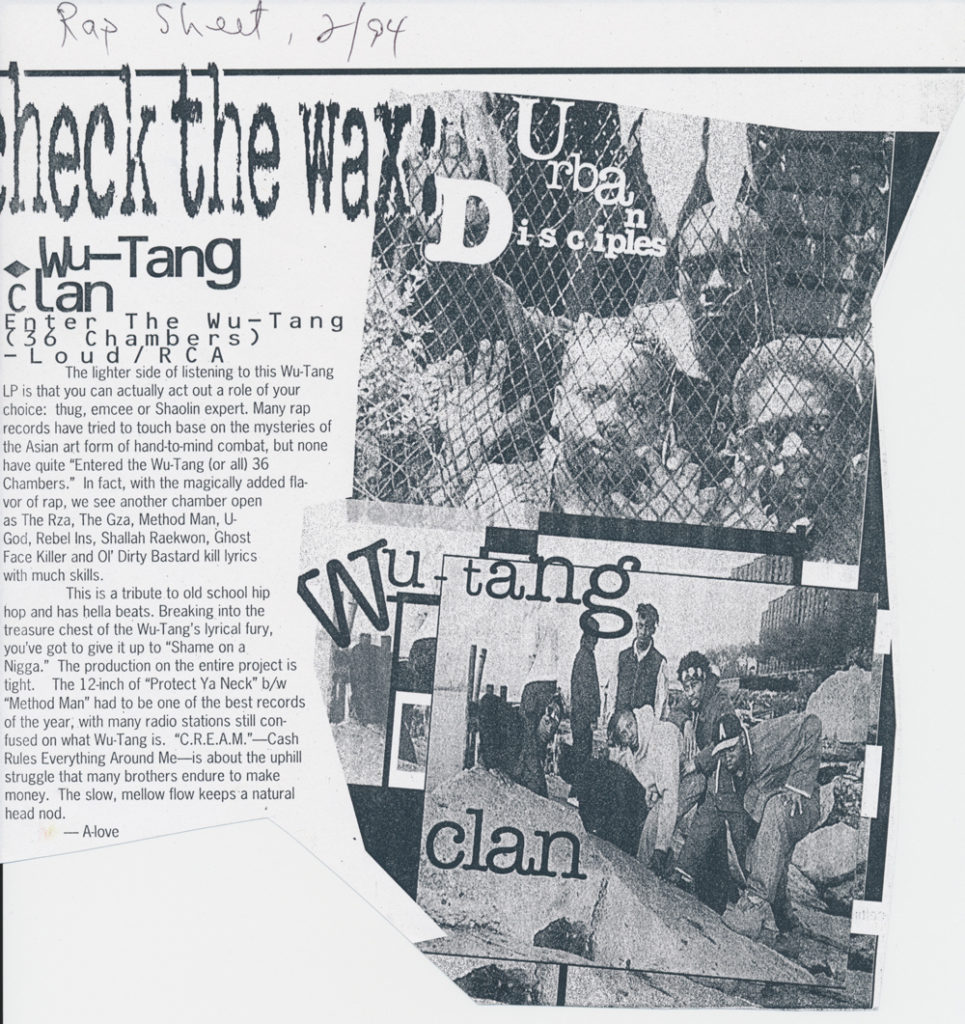

One of the first reviews of Enter the Wu-Tang appeared in the February ’94 issue of Rap Sheet magazine (below).

Written by someone calling himself, A-Love, it is very short, not to say perfunctory, but it does describe “Protect Ya Neck” as “one of the best records of the [previous] year.”

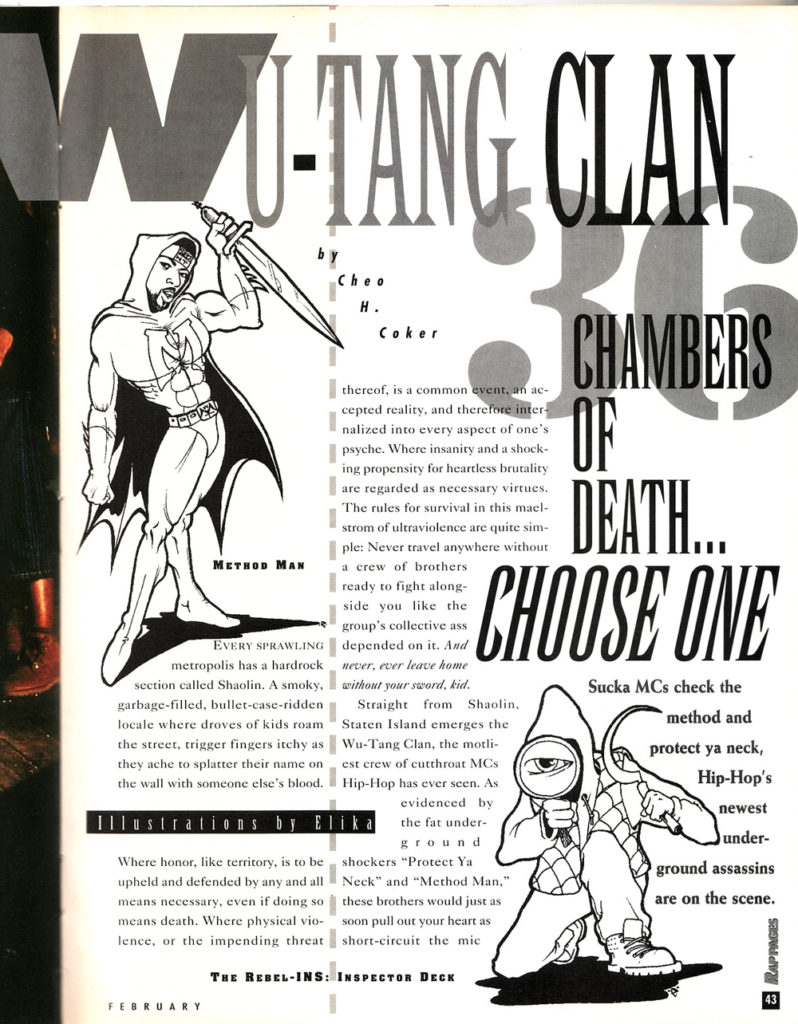

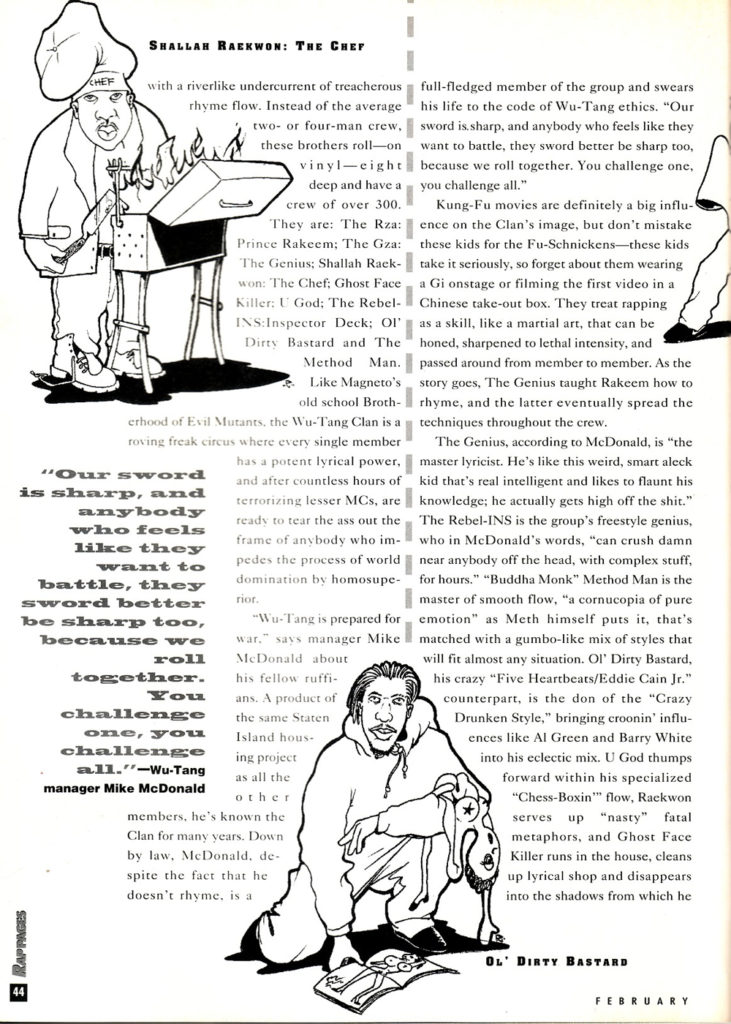

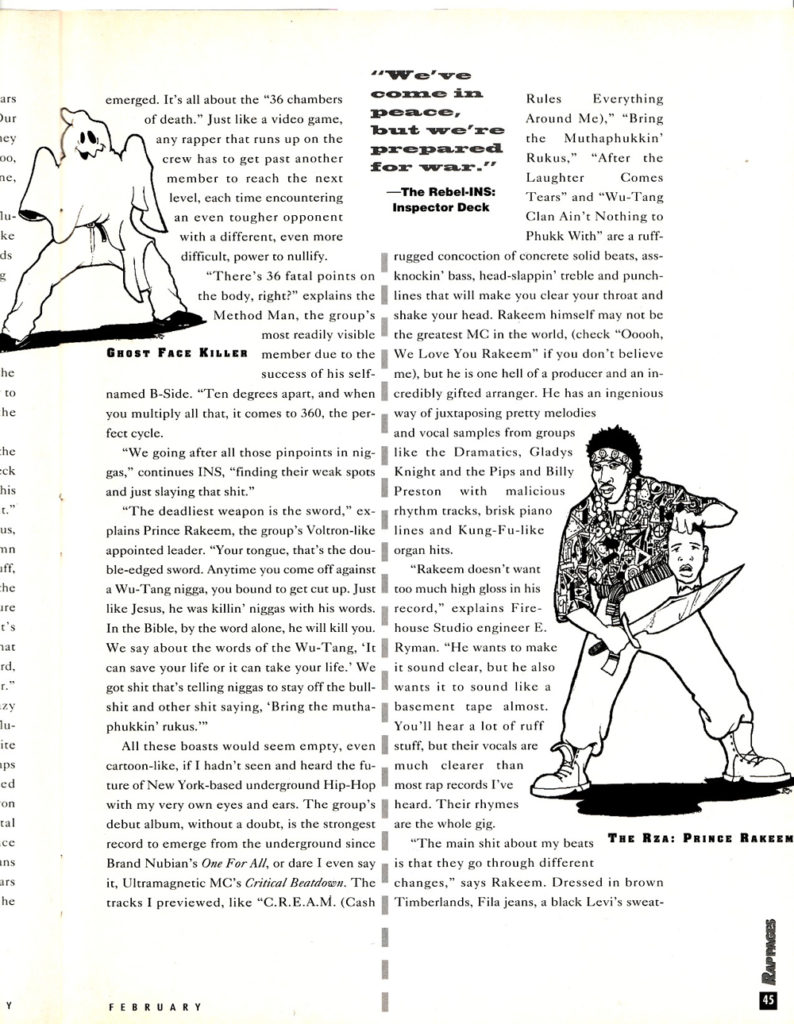

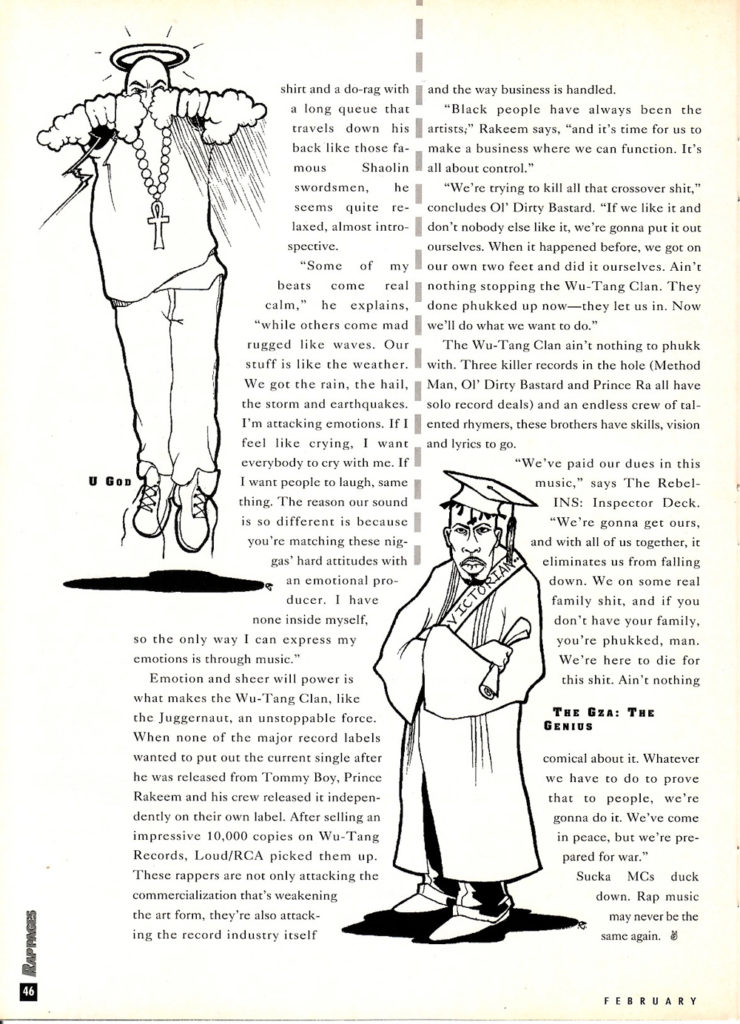

Not to be outdone, Rap Sheet’s crosstown L.A. rival, Rap Pages, published a feature story about the Wu-Tang Clan by Cheo Coker that was a full four-pages long.

These days Cheo is a big-time Hollywood writer and producer. His credits include “Southland” and ”NCIS: Los Angeles.” He also wrote the screenplay for “Notorious,” the 2009 feature film about Biggie Smalls, which was largely based on his wonderful 2003 book, “Unbelievable: The Life, Death, and Afterlife of the Notorious B.I.G.” But Cheo was a player right from the start, writing about rap not only for Rap Pages, but for The Source, XXL, Spin, Essence, The Face, and the Village Voice.

His Rap Pages piece is likely the earliest feature story ever devoted to the Wu-Tang Clan. It is very admiring of the guys themselves and even more admiring of Enter the Wu-Tang, which he calls “the strongest record to emerge from the underground since Brand Nubian’s One for All or Ultramagnetic’s Critical Beatdown.”

You’ll note, though, that the article is accompanied by illustrations of the members of the Wu by someone named Elika. That these illustrations are cartoonish is not a problem. The problem is that these cartoons owe more to “Archie” than to “Batman.”

But Cheo didn’t know there was a problem until he met again with the Wu-Tang, this time on May 12, when he intended to interview them for Mouth 2 Mouth, a short-lived teen magazine published by Time Inc. In fact, the encounter turned out to less Mouth 2 Mouth than Fist 2 Eye, which was the headline of a column about the attack written by Toure for the Village Voice

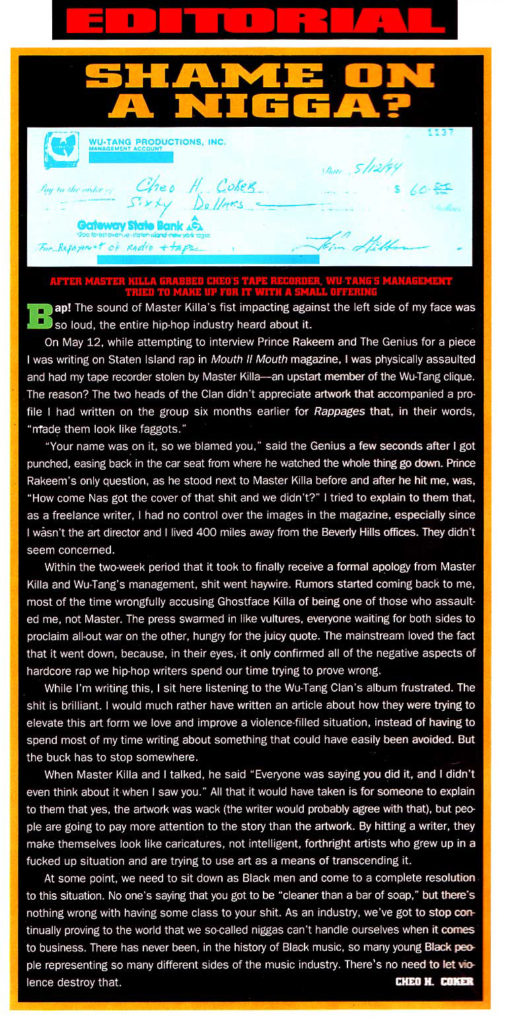

Cheo himself went on to write about the incident in an editorial headlined, “Shame on a Nigga?” that ran in The Source in August of ’94.

In it he reports that the real problem – in the opinion of the Wu-Tang Clan themselves – is that the illustrations “made them look like faggots.” The tone of the piece is marked by Cheo’s regret and frustration that he has to address this kind of problem in the first place. And he concludes on a brotherly note: “As an industry, we’ve got to stop continually proving to the world that we so-called niggas can’t handle ourselves when it comes to business.”

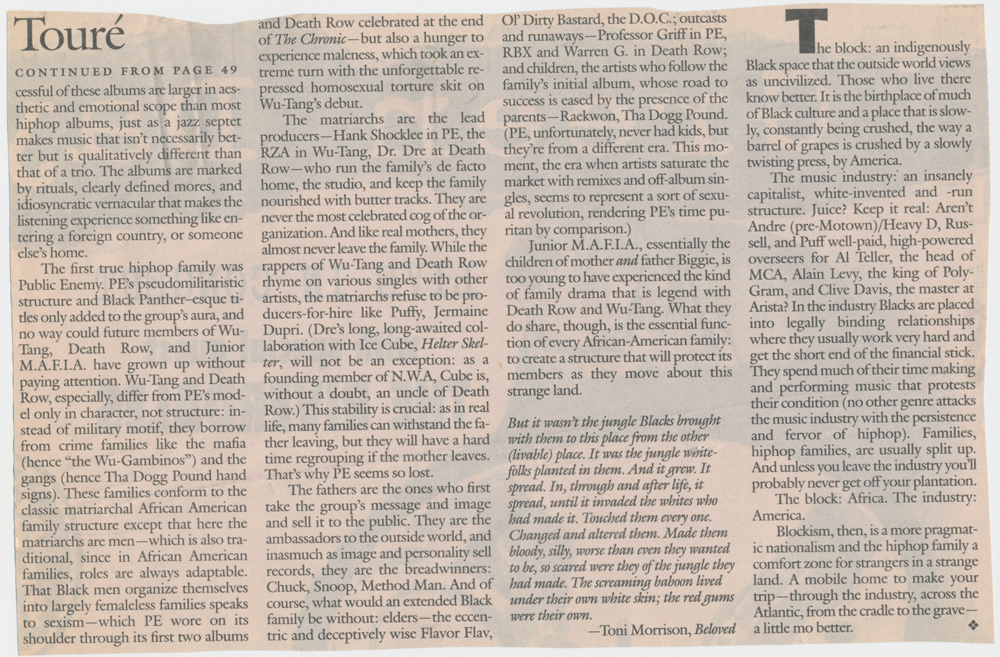

Just a few months later, Toure took critical analysis of the Wu-Tang Clan to a whole other level. In a lengthy feature for the Village Voice, he used the release of Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx and Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s Conspiracy as a launching pad for a new theory about the structure and psychology of the big then-new rap crews.

These days we know Toure as a fairly ubiquitous talking head on tv. He is the host of Fuse’s “HipHop Shop” and “On the Record” and co-host of MSNBC’s “The Cycle.” Back in the Nineties, he wrote not only for The Voice, but for The Source, XXL, Rap Pages, Spin, Essence, and for the English magazine The Face.

Here Toure goes deep. in his opinion, The Wu-Tang, J.U.N.I.O.R. Mafia (a/k/a Biggie Smalls’s crew), and the Suge Knight’s Death Row clique each comprised a hiphop family. All of them were following in the wake of “the first true hiphop family,” Public Enemy, differing from PE’s model “only in character, not structure.” He calls this phenomenon Blockism.

Cheo had suggested something similar in his piece for Rap Pages. “The rules for survival” in the hardrock section of every sprawling metropolis – Staten Island’s Stapleton Projects, in the Wu-Tang’s case — “are quite simple: Never travel anywhere without a crew of brothers ready to fight alongside you like the group’s collective ass depended on it. And never, ever leave home without your sword, kid.”

Cheo then went on to quote Inspector Deck as follows: “We on some real family shit, and if you don’t have your family, you’re fucked, man.”

But here’s Toure:

These families conform to the classic matriarchal African American family structure except that here the matriarchs are men – which is also traditional, since in African American families, roles are always adaptable. That black men organized themselves into largely female families speaks to sexism…but also to a hunger to experience maleness.

Toure ends with a very sympathetic, even lyrical, appreciation of the hip-hop-crew-as-family, by way of explaining why RZA decided to keep the music business at arm’s length and to rely on his homies instead:

Blockism, then, is a more pragmatic nationalism and the hiphop family a comfort zone for strangers in a strange land. A mobile home to make your trip – through the industry, across the Atlantic, from the cradle to the grave – a little mo better.

Whether or not this theory strikes you as deeply insightful or wildly fanciful, it is not standard hip hop critical discourse. I emailed Toure recently wondering why it didn’t earn him a punch in the eye when it was first published.

“I heard, much later, that some folks wanted to beat me up for that. But they never did. Maybe they didn’t know where to find me,” he replied. “Also The Voice was not a prime concern for those folks and their friends. That same piece in The Source would’ve been war, but The Voice was largely invisible to them.”

##

Editor’s Note: This is the ninth in a series of Bill’s “Diggin’ In The Files” posts on CrazyHood.com. Known to his co-conspirators as Ill Badler, Bill was the founding director of publicity for Def Jam Recordings and Rush Artist Management, a position he held from 1984 through 1990, during which time he promoted the careers of hip-hop legends Run-DMC, the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, LL Cool J, 3rd Bass, Slick Rick, and many others.

All images courtesy of Adler Hip-Hop Archive. Thanks for research assistance to Shawn Setaro, executive editor of RapGenius, Ben Ortiz of Cornell University’s Hip-Hop Collection, and Chairman Jefferson Mao, curator of Ego Trip‘s extensive archive of hip-hop magazines.