MOTHER SUPERIA – DA ROCK BOTTOM (INTERVIEW)

Words & Interview By Jake Paine

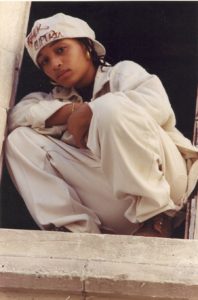

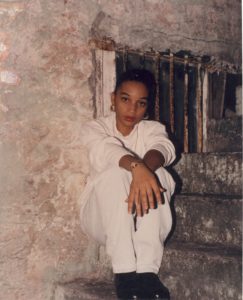

Somewhere between the bass-backed First Amendment trailblazing of Uncle Luke and the boisterous thuggery of Trick Daddy is Mother Superia. Putting “the Bottom” (as she knew it) on the map, this Rap visionary dismissed notions of fortune and fame from the beginning, simply enjoying a therapeutic outlet to release her perspectives as a B-girl growing up in Miami in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

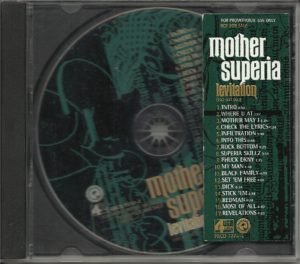

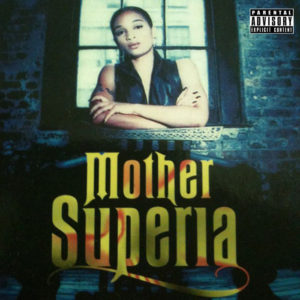

Years before Trina’s own rise to stardom, Mother Superia was not only opening up shows, she was tearing them down. Proving Miami’s naysayers wrong, this MC was winning over friendships and accolades from the likes of everybody from GZA to KRS-One. Eventually signing an album deal with Island Records in the mid-‘90s, the artist went to work with her peers, and prepared Levitation, an LP boasting work from Redman, Blastmasta, and many other esteemed peers. Despite a GZA-directed video, various singles serviced to DJs and radio, it just never happened as planned. A mother since before the deals, Superia returned home, and put music in the backseat.

Approaching 20 years since the pinnacle, Mother Superia has reason to reflect. A recent return to her craft has affirmed that kicking verses is not unlike cycling. With a book in tow, her album released digitally to the fans, and a host of new material on the horizon, one of Miami’s versatile voices is approaching the microphone yet again, with even more to say.

Approaching 20 years since the pinnacle, Mother Superia has reason to reflect. A recent return to her craft has affirmed that kicking verses is not unlike cycling. With a book in tow, her album released digitally to the fans, and a host of new material on the horizon, one of Miami’s versatile voices is approaching the microphone yet again, with even more to say.

Crazy Hood: I want to begin with gathering some of your earliest, most pivotal memories of Hip-Hop culture and the music scene within Miami during your most integral years…

Mother Superia: Well, I would say back in the early ‘80s, there would be all of these jams—we’ll call ‘em “Jams.” In Miami, Bass music is a really big thing. The thing about it is it would be like Jam Pony [Express] DJs, where cats would just bring out massive amounts of speakers, walls of them, like 30-50 speakers [stacked] super-duper high. When you’d stand in front of them the bass was so loud that your whole body would shake. The DJ crews would battle each other to see who had the loudest [display] of speakers. That’s a different kind of thing, being from Miami. People from New York…my husband, he’s from Brooklyn, and they had jams in the park, and the DJ battles, [but the bass-centered battle] was our thing. That was my experience as a young, young kid.

Later on, I was in a foster home that was down in Homestead/Florida City. There was a couple of groups. One group was called BVSMP, and they had a Power 96 kind of song called “I Need You.” During that time, was when I actually starting rapping. There was some girls who dated some guys and we would all get together, hang out, and one of the girl’s boyfriends had a couple of turntables at the house, and some microphones. That was my first, “Aw yeah, this is something that I’m really into” [moment].

Crazy Hood: What were some of the records involved in those early DJ battles?

Mother Superia: Some of the stuff is the same [as what was played in New York], like [Sugarhill Gang’s] “Rapper’s Delight,” that made it all the way down to Miami, and all over the world, of course. Then The Egyptian Lover’s [“Egypt, Egypt”], and of all that [Freestyle] music. And of course you can’t talk about Miami without talking about 2 Live Crew , MC Shy D , Gucci Crew II, JT Money and Poison Clan.

https://youtu.be/_upyP50W22o

Crazy Hood: At what point did you truly realize that you were gifted as an MC?

Mother Superia: I don’t ever think it was a dream of mine, ‘cause I wasn’t really dreaming about it. I was living in the moment of it, blossoming. I was never really conscious of this that [it was a goal for a career]. I was just doing it. Maybe if I had a different mindset about it more than just an artistic expression and an outlet and a lifesaver for me at times, maybe I would have made some money at it. [Laughs] I never thought about it like that. I’ve always been a very rambunctious personality type, never docile. I knew that I was good at it. I knew that it allowed me to be aggressive without being physically aggressive, and I liked that about it. But I think when I realized that this shit was for-real, for-real, is when Wu-Tang [Clan] came to Miami. I opened for them at the Mahi Temple. Mind you, I’d done a bunch of other shows…I’d opened for A Tribe Called Quest, Black Moon, Ultramagetic [MC’s], and I don’t want to minimize those things, because those were awesome as well. But the Wu-Tang show…maybe it’s because I got paid that night, and the show was in Mahi Temple, so it held a lot more people than a nightclub. I just knew that I had it at that point, like “Oh shit!” I just went out there by myself, not with a bunch of people on the stage. It was just me and DJ Coupe DeVille for like 30 minutes—me and Cooper, that’s it! When I came off the stage, [Wu-Tang Clan] was like, “Damn, shorty, that was you up there by yourself?” Later on, some of us became cool, and hung with each other. But yeah, that was the show where I was like, “Yeah, they can’t fuck with me.”

Mother Superia: I don’t ever think it was a dream of mine, ‘cause I wasn’t really dreaming about it. I was living in the moment of it, blossoming. I was never really conscious of this that [it was a goal for a career]. I was just doing it. Maybe if I had a different mindset about it more than just an artistic expression and an outlet and a lifesaver for me at times, maybe I would have made some money at it. [Laughs] I never thought about it like that. I’ve always been a very rambunctious personality type, never docile. I knew that I was good at it. I knew that it allowed me to be aggressive without being physically aggressive, and I liked that about it. But I think when I realized that this shit was for-real, for-real, is when Wu-Tang [Clan] came to Miami. I opened for them at the Mahi Temple. Mind you, I’d done a bunch of other shows…I’d opened for A Tribe Called Quest, Black Moon, Ultramagetic [MC’s], and I don’t want to minimize those things, because those were awesome as well. But the Wu-Tang show…maybe it’s because I got paid that night, and the show was in Mahi Temple, so it held a lot more people than a nightclub. I just knew that I had it at that point, like “Oh shit!” I just went out there by myself, not with a bunch of people on the stage. It was just me and DJ Coupe DeVille for like 30 minutes—me and Cooper, that’s it! When I came off the stage, [Wu-Tang Clan] was like, “Damn, shorty, that was you up there by yourself?” Later on, some of us became cool, and hung with each other. But yeah, that was the show where I was like, “Yeah, they can’t fuck with me.”

Crazy Hood: I’ve always admired your style that it knows no place and time. Plus, if I don’t know your story, I don’t hear a sound and style that immediately says Miami. In those days, did you get the sense that people traveling through had a preconceived idea that artists from the area were limited?

Mother Superia: Miami is a very eclectic place. Black people, white people, and all kinds of Spanish people, and all kinds of Island people, and then there’s a lot of New York [transplants]. It would be amongst those MCs—the Miami MCs—that would say shit like, if you were a Miami rapper, they’d call you a “Yo My Nigga.” ‘Cause that was a thing that people who were native to Miami said. “All these Yo My Niggas,…” etc. But I’d be with these northern people, yet I’d be one of the people who was from here, and [I would correct them]. Within the community, that would always be [present]. It really drove me to…when I saw a cipher of people of freestyling, I’d walk over there [and include] “Miami” and “305” [in my raps]. It’s a thing that boosted me.

A lot of people that were bigger than the local acts were a little bit surprised by us, and they weren’t dismissive. I think they were just surprised once they heard it. “Oh shit, this is not just some booty-shaking, talking about ‘Pop That Coochie,’” or whatever the case may be. “Wow, this girl can really rap. She’s an MC.”

Crazy Hood: When you opened up for Wu-Tang Clan, you’d coined your stage name? I’d love to know the story behind that…

Mother Superia: Well…before the whole Mother Superia thing, I was “MC SLS.” My name is Sonya Levette Spikes. I was that for a hot minute, early high school or something. And then when I was in that foster home, there was this security guard in school, her name was Mrs. True. I don’t know where she is, but I’d love to see her though. She always used to look out for me, invite me over to her crib, did her on the side and whatever. When my mother came home, me and the lady stayed in contact with each other. She went to a different school. She met a girl there, and this girl, her name was Sandy, and she was from New York. She could rap, freestyle. So me and the girl met, and we had a group. Our group was called S2—like S to the second power. She was Sandy, and I was Sonya. She was “Supreme” and I was “Superia.” So that was our group. Then when I got pregnant, I think her parents were freaked out—“Oh, you better stop hangin’ out with her.” So we went on our separate ways; we remain friends, outside of music. So I kept “Superia,” but I’d had a baby, so I’d call myself “Mother Superia.” [I caught some flack from that]. Even KRS-One was like, “Why don’t you just go by Superia?” I wasn’t listening. [Laughs]

Mother Superia: Well…before the whole Mother Superia thing, I was “MC SLS.” My name is Sonya Levette Spikes. I was that for a hot minute, early high school or something. And then when I was in that foster home, there was this security guard in school, her name was Mrs. True. I don’t know where she is, but I’d love to see her though. She always used to look out for me, invite me over to her crib, did her on the side and whatever. When my mother came home, me and the lady stayed in contact with each other. She went to a different school. She met a girl there, and this girl, her name was Sandy, and she was from New York. She could rap, freestyle. So me and the girl met, and we had a group. Our group was called S2—like S to the second power. She was Sandy, and I was Sonya. She was “Supreme” and I was “Superia.” So that was our group. Then when I got pregnant, I think her parents were freaked out—“Oh, you better stop hangin’ out with her.” So we went on our separate ways; we remain friends, outside of music. So I kept “Superia,” but I’d had a baby, so I’d call myself “Mother Superia.” [I caught some flack from that]. Even KRS-One was like, “Why don’t you just go by Superia?” I wasn’t listening. [Laughs]

Crazy Hood: What year and time was your first contract?

Mother Superia: Before Island Records, there was this company down on the south side of Miami, Blue Entertainment or something—we were about to sign with them, and then I got pregnant. The next deal would have been with Island Records, and that would have been 1994, 1995—somewhere in there.

Crazy Hood: Recently, we interviewed Brother J from X-Clan, one of your former label-mates. I don’t mean to kick Island/4th & Broadway in the ribs How much do you think where you sign a contract affects your career and trajectory?

Mother Superia: I think it really depends on who is the person that signs you to the label, and how much the label is behind you makes the most difference. I think it is important. You want to be on a label that will market and promote—a label that is into artist development because they know that that shit is important, to set the stage for some sort of longevity. I would yeah, it’s really important. The label itself, and also the people at the label—is this just a job for them, or do they have a love for the music as well?

Crazy Hood: In 1994, to be on Island, label-mates with Rakim, what was it like to go from the dedication of having this form of release, Levitation, to going on to executing your vision?

Mother Superia: I was excited to have the opportunity. I had never been to New York before, so when we got there, of course I’m on the damn highway, seeing like Linden Boulevard and Farmers Avenue, being like, “Oh shit, from the records!”

[Sighs] It’s hard to explain. At the time…like the dude who signed me was Joe Galdo—love Joe to death, to this day. He signed me to Island, but somehow the music came out on 4th & Broadway. I guess that was their Rap division or what have you. So the people like Rakim and these folks that were on Island or the subsidiaries, I never got to know them or kick it with them. It was much politics. This one guy from the Black Music Department over at Island was [on some] “I’m not really trying to fuck with this girl ‘cause I didn’t sign her.” The dude who signed me wasn’t an A&R who could take me and develop me, ‘cause it was Black Music, and [Joe] was this Cuban guy down in Miami, who’s running this studio out of this place. He’s working with people like Grace Jones, doing some real other artsy kind of musical, instrumentational, off-the-wall kind of shit. So I got stuck with this other dude. So I don’t know…I don’t even know what you asked me now…wa

Crazy Hood: I think you answered the question, and I appreciate your openness. Was your opening for Wu-Tang relationship what ultimately led to GZA directing your music video?

Mother Superia: Yes. Definitely so. And it’s not like GZA directed a whole bunch of videos, you know what I’m saying? It was just like that these dudes were super cool with me; it was organic. Later on, when I came to New York, GZA was like, “Well, I’m right here in Brooklyn. Why don’t we get together and do a treatment?” We sat over by the park, we smoked, we went over to the house and played Jenga. His girlfriend was hella cool. The same [organic friendship and support was true of] KRS-One too.

Crazy Hood: Redman was also an integral part of your album, and in a capacity he’s not traditionally remembered for: production…

Mother Superia: My manager when I got my deal was a lady named Sandy Griffin. She was in with the whole EPMD and Redman and K-Solo and all of that. Of course I’m a Redman fan, so I was like, “Aw, I’d love to do a song with this guy.” She was like, “For real? That’s no problem.” And that’s exactly what happened. We went to some studio over in Long Island, Rockin Reel [Studios]. No food…we had like one cheeseburger; we’d been smoking, we’re starving. We put the cheeseburger into the microwave and cut it up into little pieces, pretended it was steak, like, “this is great!” We just did the music together.

Crazy Hood: Eighteen years later, what relationship do you have with that album? Is it something you listen to?

Mother Superia: For a long time, I don’t think I even had a full copy of it, to be honest with you. I reached out to Joe Galdo, and he sent me two copies: the green copy, and the gold copy. There were two copies; I’ll tell you why that was the case. But the Internet is awesome, so [it’s available on iTunes now]. I do listen to it, but I don’t listen to it all the time. There is some frustration, but when I listen to it, it’s a source of joy and a definite ego-booster. I thump my chest a lil’ bit. [Laughs] So the green and the gold one [difference] is I shouted out a lot of dates on one, “1996, this that,” on a couple tracks. So we had to go back in and take some of that stuff out.

Crazy Hood: 1996 was an interesting year for women in Hip-Hop. You had artists like yourself, Bahamadia, The Lady Of Rage, Heather B, Mia X, and so forth really making noise, amidst veterans like MC Lyte, Yo-Yo, and Queen Latifah going strong, but also Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown emerging. At the time of your recording, did you realize you were in such a cultural intersection at the time?

Mother Superia: Oh yeah, ‘cause people were asking [about] it. They were saying it. Somebody sent me a link of this [panel] from a long time ago; we went and spoke at some high school. Wendy Williams was there. They did this whole thing about female rappers [and whatnot]. Of course, me being who I am, I’m not gonna be like, “My concern for the Black community…”—not that I don’t have that concern now. But there was a time where it was, “these young Black dudes are getting killed everyday, and women have so much power. If we would just use that to make these men be different, we could do that. Instead, it’s used to [propagate] the latest [fashions and hustles].” That was a part of that interview. I was right on the [cusp]. The dude who signed me, Hiram Hicks, was the one who was Head Of Black Music at Island [Records] at that time, they wanted me to record another album. But they wanted me to record something that wasn’t—they told me, “The record industry doesn’t need another Lauryn Hill, they already have one of those.” I said, “Well, first of all, I don’t sing. I may have the same kind of heavy voice, but the flow is totally different.” They wanted me to record something that was more in the vein of Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown; some of the producers that they sent me to and the samples that were so apparent in the music—it wasn’t like samples that somebody had creatively flipped. At that time, it was the whole [Shiny Suit Era]. So that happened. I never recorded the other record. I went home.

Women are all of those things. We can be that sexual thing. It’s unfortunate, but this is the world that we live in. That is what women have to do in the urban music community, more so than any other music community, in order to sell some records.

Crazy Hood: You’ve still made music since then. Tell me about your life, times, and career after Island…

Mother Superia: Since then, folks have called me to do projects. A couple of the guys I worked with on the Levitation album, my homeboy Sonny Black—it was cool to work with him again on his project. When I was in New York, I did some work with independent producers and did some stuff there. I have those recordings. My son, who’s now 23 [years old], is on a couple of those tracks. It’s just interesting to be able to play that back like, “Listen to you. You were a baby, and now you’ve got a deep voice and hair on your face.” That’s cool. Then, when I came here to Georgia, I used to host a bunch of parties, which was interesting. They have the Apache Café here in Atlanta, that’s really popular. We go to that, and they have this open mic. Mind you, I haven’t did music in a long time. I’m kinda bummed out, had a lil’ baby. I’m like, “I don’t even know if I still got it. Whatever. I’m gonna get in this open mic and see what happens.” We go, and there’s probably 50 MCs in there. I make it all the way to the end to the last four MCs. I know I killed this dude! I made it to the last one. So yeah, I know I still got it. That was an experience. Freestyling is my first love. It’s so much fun.

Mother Superia: Since then, folks have called me to do projects. A couple of the guys I worked with on the Levitation album, my homeboy Sonny Black—it was cool to work with him again on his project. When I was in New York, I did some work with independent producers and did some stuff there. I have those recordings. My son, who’s now 23 [years old], is on a couple of those tracks. It’s just interesting to be able to play that back like, “Listen to you. You were a baby, and now you’ve got a deep voice and hair on your face.” That’s cool. Then, when I came here to Georgia, I used to host a bunch of parties, which was interesting. They have the Apache Café here in Atlanta, that’s really popular. We go to that, and they have this open mic. Mind you, I haven’t did music in a long time. I’m kinda bummed out, had a lil’ baby. I’m like, “I don’t even know if I still got it. Whatever. I’m gonna get in this open mic and see what happens.” We go, and there’s probably 50 MCs in there. I make it all the way to the end to the last four MCs. I know I killed this dude! I made it to the last one. So yeah, I know I still got it. That was an experience. Freestyling is my first love. It’s so much fun.

Buy Levitation here.

Jake Paine has been a music industry professional since 2002. In addition to five years as HipHopDX.com’s Editor-in-Chief, Paine spent five years as AllHipHop’s Features Editor. He has written for Forbes, XXL, The Source, Mass Appeal, among others. He currently resides in Pittsburgh.